The Plains Bison: Comeback of a Lost Giant

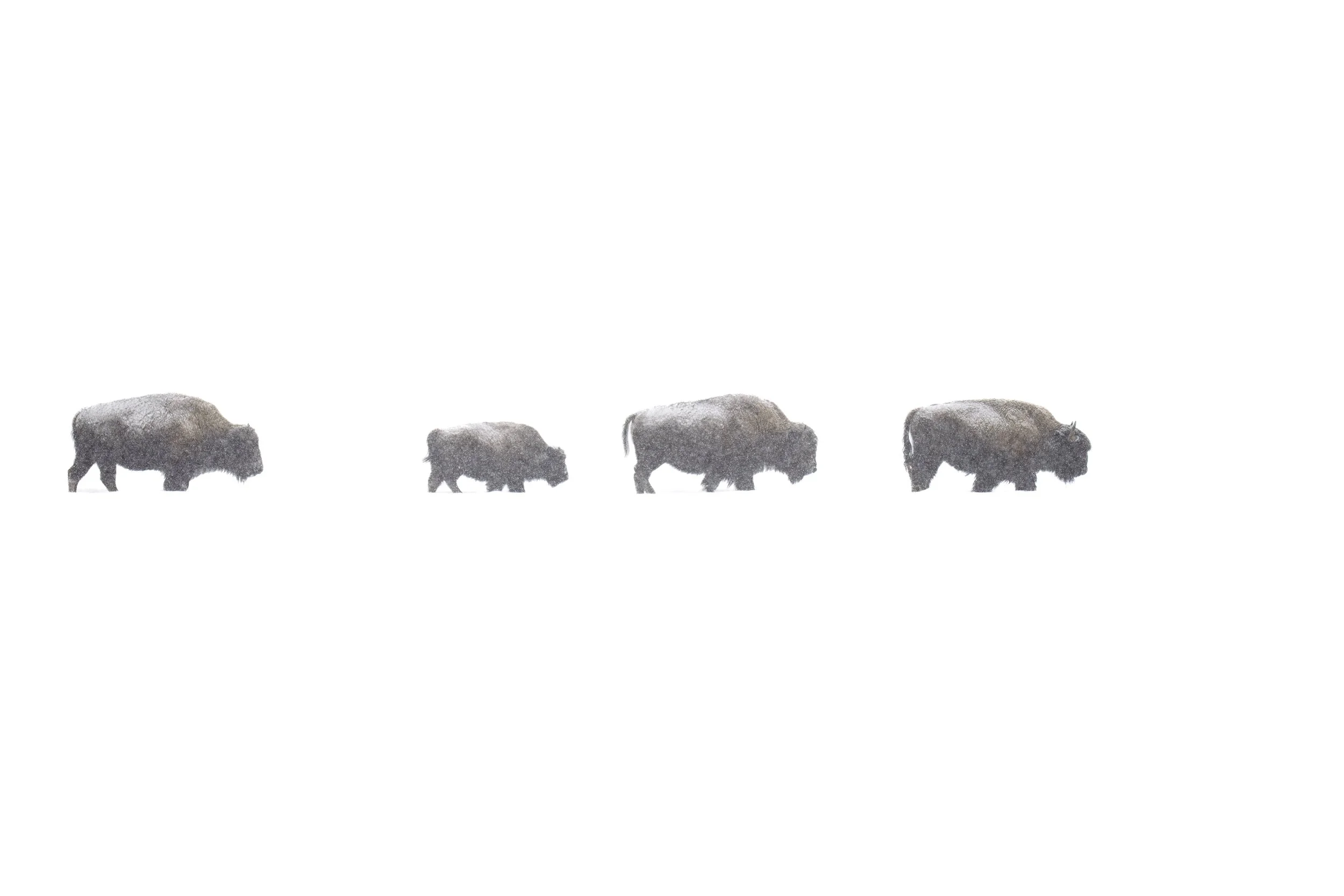

This sight—a frost-covered bison with snow flying from his hooves, charging across a snowy landscape—is a sight that once teetered on the edge of disappearing forever.

Steam rises from his nostrils as he exhales, his breath catching in the crisp morning air. His hooves, the same ones that have shaped North America’s prairies for tens of thousands of years, churn through the drifts with a slow, deliberate rhythm. He is the embodiment of a past nearly erased, a living relic of an era when millions of his kind once thundered across the plains in herds so vast they stretched to the horizon.

The survival of the American plains bison (Bison bison bison) is one of the most improbable conservation victories in history. From a population that once numbered between 30 and 60 million, these great beasts were slaughtered to near extinction in the span of a few decades. Their disappearance was not an accident of history, nor was it the simple consequence of overhunting—it was a calculated destruction, fueled by market forces, government policy, and a broader effort to subjugate Indigenous nations who depended on the bison for survival.

That the bison exist at all today is due to a patchwork of efforts—some driven by conservationists, some by wealthy landowners, and others by Indigenous nations who never gave up on restoring the sacred animal to its rightful place. And at the heart of it all is Yellowstone National Park, the only place in the lower 48 states where wild bison have survived continuously since prehistory.

A Giant Falls: The 19th-Century Slaughter of the Bison

Before the arrival of Europeans, the bison shaped the very land they roamed. Their hooves aerated the soil, their grazing patterns encouraged the growth of nutrient-rich grasses, and their carcasses sustained entire ecosystems of scavengers and predators. For thousands of years, the Indigenous peoples of North America lived in deep reciprocity with the bison, hunting them with skill and reverence, ensuring that the herds would always return.

But by the mid-1800s, that delicate balance—one that had persisted for thousands of years between bison, grasslands, and the Indigenous nations that depended on them—was violently undone. The rapid expansion of transcontinental railroads carved deep wounds into the heart of the Great Plains, allowing commercial hunters, market traders, and settlers to penetrate lands once ruled by the rhythms of nature. Technological advancements in firearms, particularly the advent of breech-loading rifles and high-powered long-range Sharps rifles, turned slaughter into an industrial operation. No longer did a hunter need to approach a herd with skill and patience; from the raised embankments of the railways, they could fire indiscriminately, bringing down dozens of animals in a single afternoon.

Bison hides quickly became one of the most sought-after commodities in the global leather trade. European and American manufacturers clamored for the thick, durable skins, particularly in the wake of industrialization, when leather belts were needed to power factory machinery. Where once an animal had been honored in its entirety—its meat, bones, sinew, and hide providing food, shelter, tools, and clothing for Indigenous nations—commercial hunters saw only profit. Carcasses, stripped of their skins, were left to rot under the unrelenting prairie sun, their skeletal remains forming ghostly white drifts across the plains.

But this was not just an economic boom; it was an act of warfare. The U.S. government, already engaged in violent campaigns to wrest control of the West from its original inhabitants, saw the destruction of the bison as a means to an end. The great herds were not just a food source for Plains tribes but the foundation of their entire way of life, from sustenance to spirituality to trade. By eradicating the bison, the government sought to sever that lifeline.

No figure embodied this brutal strategy more than General Philip Sheridan, a key architect of the Indian Wars. He openly endorsed the extermination of bison as a means of starving Indigenous nations into submission, reportedly telling hunters, “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” Under this policy of deliberate ecological devastation, military officers, traders, and settlers worked in concert with commercial hunters to bring the bison to the brink of extinction. Sheridan even argued against laws that sought to curb the slaughter, insisting that “these men have done more in the last two years, and will do more in the next year, to settle the vexed Indian question than the entire regular army has done in the last thirty years.”

And so, in the span of just a few decades, an animal that had once numbered in the tens of millions was reduced to a few hundred scattered survivors. The great herds that once rumbled like distant thunder across the grasslands—an ecological force shaping the continent itself—vanished. The Plains, once animated by a symphony of hooves and breath, fell silent. The bison had been sacrificed on the altar of Manifest Destiny, their absence marking a turning point not only for Indigenous nations but for the land itself.

By the late 1880s, the vast herds had been reduced to a few scattered survivors. In the entire United States, fewer than a thousand bison remained—most of them hidden in isolated pockets, out of sight and out of mind.

One such pocket was Yellowstone National Park. Established in 1872 as America’s first national park, Yellowstone was home to a small, secretive herd of wild bison that had somehow managed to avoid the slaughter. But their existence was precarious—by 1902, only 23 wild bison remained in the park, tucked away in the remote, snowbound Pelican Valley.

Early park rangers, understanding the gravity of the situation, took it upon themselves to act as the last line of defense. Armed with rifles, they patrolled Yellowstone’s windswept valleys and dense lodgepole forests, determined to protect the few surviving bison from poachers who sought to finish what commercial hunters had begun. Each winter, they fought a war of attrition—not just against the relentless cold, but against the very real possibility that the species would vanish entirely. Their efforts, however, were little more than a desperate holding action. With so few animals left, the genetic bottleneck was tightening. Without a more deliberate intervention, the Yellowstone herd would not survive.

William Temple Hornaday Enters the Story

A taxidermist by trade but a conservationist by conviction, William Temple Hornaday was among the first Americans to sound the alarm over the impending extinction of the bison. In 1886, he embarked on what he initially viewed as a scientific expedition, traveling west to collect specimens for the Smithsonian Institution. What he found was not the sprawling herds that had once stretched from horizon to horizon, but an empty, wind-scoured prairie littered with the wreckage of slaughter—sun-bleached skulls, disarticulated bones, and the occasional half-rotted carcass, left where it had fallen. The sight unsettled him. What had once been one of the defining forces of the continent’s ecology had been reduced to a mere handful of ghosts clinging to survival in Yellowstone and a few scattered pockets of the West.

Hornaday understood that science alone could not catalog what no longer existed. In an era where taxidermy often served as the final act of a species, he made a radical choice: instead of merely preserving the bison in glass cases, he would try to preserve them in life. He gathered the last remaining individuals he could find, capturing a small group and bringing them east to form the nucleus of what would become one of the first concerted captive breeding programs. His efforts laid the groundwork for the American Bison Society, an organization dedicated not just to saving the species from extinction, but to restoring it to the landscape from which it had been so violently erased.

Hornaday’s vision extended beyond Yellowstone’s fragile remnant herd. He championed the idea of introducing bison to private ranches, reserves, and, eventually, public lands, recognizing that survival in captivity alone was not enough. The bison, he believed, must return to the open spaces that had shaped them for millennia. It was an idea that would prove critical in the decades to come, as wild populations began a slow, improbable recovery—a recovery that, like the animal itself, stood as an act of defiance against the forces that had nearly driven it into oblivion.

Teddy Roosevelt and the Politics of Conservation

Another key figure in bison conservation was Theodore Roosevelt, a lifelong hunter who became one of America’s most influential conservationists. Roosevelt, like Hornaday, was alarmed by the rapid disappearance of the bison. As president, he helped pass laws protecting Yellowstone’s bison from further poaching and was instrumental in establishing the first federally managed bison reserves.

Roosevelt’s policies laid the groundwork for modern wildlife conservation, but he wasn’t alone. Ranchers such as Charles Goodnight, a former Texas cattle baron, played an unexpected role as well. Goodnight, recognizing the historical and ecological value of bison, captured some of the last remaining wild individuals and bred them on his ranch. His efforts, though initially driven by profit, ultimately helped preserve the species by providing stock for later reintroductions.

Indigenous Nations and the Fight to Restore the Bison

While men like William Hornaday, Theodore Roosevelt, and Charles Goodnight were instrumental in preventing the bison’s outright extinction, the deeper, longer fight for true restoration belonged to the Indigenous nations of the Plains. Their relationship with the bison was not simply one of utility; it was spiritual, ecological, and cultural, woven into the very identity of their peoples. When the herds were slaughtered, it was not just an ecological catastrophe—it was an act of cultural erasure, a calculated attempt to sever Indigenous nations from their land, their traditions, and their sovereignty. Yet despite decades of forced removals, broken treaties, and federal policies designed to assimilate or annihilate them, these nations never abandoned their bond with the bison.

For the Lakota, Blackfeet, Nez Perce, Assiniboine, and many others, the fight to restore the bison was inseparable from the fight to reclaim their own autonomy. Though the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the great herds reduced to a few fragmented populations—many confined to fenced reserves—Indigenous communities maintained their cultural connection to the animal through oral histories, ceremonies, and the careful protection of small, remnant herds. In the late 20th century, as conservation efforts expanded beyond preservation and into rewilding, Indigenous leadership became increasingly central to the movement.

One of the most significant moments came in 1991 with the formation of the InterTribal Buffalo Council (ITBC), a coalition of Native nations dedicated to returning bison to tribal lands. Recognizing that many of the surviving conservation herds—including those in Yellowstone, Wind Cave, and the National Bison Range—were descendants of animals originally taken from the Great Plains, the ITBC sought to bring them home. Working alongside national parks, wildlife agencies, and private conservation groups, the council has helped relocate thousands of bison, reintroducing them not just as managed livestock, but as free-roaming animals integrated into traditional ecological knowledge.

Indigenous conservationists also forged partnerships with non-Native organizations to ensure that bison restoration was not just symbolic, but functional. The Blackfeet Nation of Montana, for example, collaborated with the Wildlife Conservation Society and Canadian parks to establish a cross-border initiative, restoring bison to lands they had once roamed freely between what are now the United States and Canada. The Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes played a pivotal role in providing sanctuary for Yellowstone bison that would otherwise have been culled, allowing them to be relocated to other tribal lands rather than slaughtered.

Today, more than 80 tribal nations manage their own bison herds, many of which trace their lineage back to Yellowstone’s last wild bison. These herds are not just ecological restorations; they are acts of sovereignty, living proof of a resilience that neither government policies nor commercial slaughter could erase. Unlike the early conservationists, who often saw the bison as a species in need of rescue, Indigenous nations see their return as something much deeper—a healing of both land and people, a reconnection of the past with the future, and a step toward a more just and balanced world.

The Modern Struggle: Bison Beyond Yellowstone

Despite their incredible comeback, Yellowstone’s bison remain under siege. Every winter, as the snow deepens and forage becomes scarce, hundreds of bison migrate beyond the park’s boundaries. And every year, they are met with hostility from state wildlife officials and ranchers who fear they will spread brucellosis, a disease that can cause miscarriages in cattle.

Although no direct transmission from bison to cattle has ever been documented in the wild (though many transmissions from elk to cattle have been documented), the fear persists. As a result, hundreds of Yellowstone bison are hazed back into the park, captured and quarantined, or killed outright. The annual culling of bison remains one of the most contentious wildlife management issues in the American West.

Yet hope remains. Conservationists and Indigenous nations continue to push for solutions that allow wild bison to roam freely beyond the park, restoring them to lands where they once thrived. Some of these efforts have already succeeded, with small herds of Yellowstone bison being relocated to places like the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in Montana.

Today, Yellowstone’s bison are more than just relics of the past—they are a living bridge between history and the future. They are proof that extinction is not inevitable, that nature, given a chance, can rebound.

Each winter, when the frost-covered bulls push through the snow, when the mothers shield their red-hued calves from the wind, they carry with them a story of near destruction and survival against all odds. They remind us of what was lost, but more importantly, of what can still be reclaimed.

The fight for bison is far from over. But as long as they roam the valleys of Yellowstone, wild and untamed, they serve as a testament to the resilience of the land—and to those who fought to save them.